People have been looking for comfort in life since the dawn of time. Winds are a well-known natural source of coolness and refreshment. In ancient times, people easily managed to create a cooling breeze by waving leaves. And so the prototype of the fan was born.

The earliest known fan survivals have been from Egyptian tombs

There is no doubt that people have been using fans since the beginning of time. But only a few have survived in modern times. Ancient fans have been found in Egyptian tombs, and therefore it is generally believed that the fan was invented in Egypt.

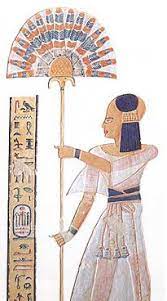

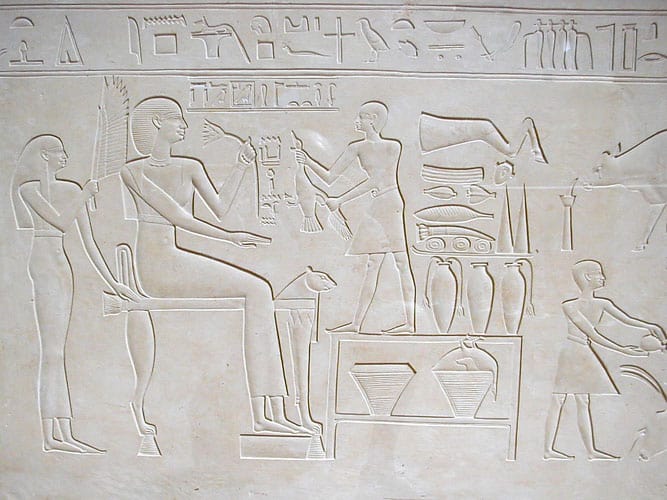

First fans were really simple – a palm leaf waved in front of the face to chill out. Later on appeared the so-called screen fans with fixed leaves. The servants of the Egyptian elites fanned them with palm leaves.

In time fans were made of elaborate materials such as gold filigree or carved mother-of-pearl. Such exquisite fans were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, elaborately crafted of gold, which also contained remnants of ostrich feathers.

The discovery was all the more fascinating because the fans found matched those depicted in paintings on the tomb walls, suggesting that they were part of the everyday furnishings of the king and his family.

These fans were also a status symbol. Richly adorned with precious stones or glass faience and elaborately decorated with scenes of battles, domestic life, or leisure activities, they represented the pinnacle of power and influence and eloquently expressed the importance of their owner.

These fans were also regularly carried by servants in royal processions at court and in religious ceremonies (their modern counterpart is the flabella, which is carried behind the pope in processions in Rome when he is seated on the sedia gestatoria).

The main features of these fans are the long handle ending in a knob at the bottom and a stylized papyrus or lotus flower at the top, a semicircular or elongated palm, and several long ostrich feathers (of a type that existed in Egypt until about 150 years ago). They were used mainly as a sunshade.

The office of fan bearer was considered one of the highest offices among court officials. In fact, the title of fan bearer was so important that it was given to the viceroy, the trusted military commander for the territory of Nubia and the Sudan.

The actual office of the fan bearer was known as “tchay khuw”. One of the earliest known persons to hold this office is Maiherperi (c. 1400 BC). He grew up in the royal nursery and was buried in the Valley of the Kings.

His fan-bearer title was of great importance, and the further designation “fan-bearer at the right hand of the king” reflects a close personal relationship with the pharaoh himself. The military connection with these officials is close, and it has been suggested that these “fan-bearers” were part of the pharaoh’s bodyguard.

Smaller, hand-held versions of these palm fiber fans were used for everyday purposes, especially for kindling domestic fire. In almost all kitchen scenes and models, at least one figure is usually engaged in stoking the flames.

Etymology, Origin, and Meaning of the Words for Fan in Antiquity

Bird feathers were used in ancient times to make elaborate fans. But the relationship between birds and fans is much deeper. Birds flap their wings and create a cooling breeze, just like waving a fan.

A fan in the form of a bird’s wing can be seen in a scene on a relief of the limestone sarcophagus of Ashayet or Ashait- ancient Egyptian queen consort, a wife of Mentuhotep II in the 11th Dynasty.

This association between birds and fans was not limited to ancient Egypt. In the Indian subcontinent, the Hindi generic term for a fan is “pankha,” derived from “pankh,” meaning a feather or a bird’s wing.

In China, the archaic symbol for a fan looks like and means a bird’s wing, and the newer word “shan” means “feathers under a roof.” In the Japanese language, the word “fan” has similar meanings.

The first Chinese fans (handshakes) were probably made of feathers, like many other early fans, and have not survived. At one point, peacock feathers were used, and then silk and sometimes silk carpets (kesi) were used for the economy.

Sometimes the tips were bent to create a better breeze. In China, both sexes wore fans, and detailed regulations assigned a specific type of fan to each rank and person. The fan was used in ceremonies and could also be used to cover the face when passing dignitaries of the same rank, avoiding the need for endless greeting rituals.

Fans in the Americas, like everywhere else in the world, were characterized by the use of bird feathers. For Aztec, Mayan, and South American cultures, feathers often had religious significance, and they were experts in the use of feathers in various art forms.

Because of the perishable nature of feathers, little of this art has survived. However, a fan-owned by Montezuma, the Aztec emperor of Mexico, is preserved in the Museum fuer Voelkerkunde in the Hofburg in Vienna. It is one of six pieces of the Montezuma treasure sent by Cortez to the Habsburg King Charles V of Spain in 1524.

Chinese Invented the Mechanized Fan in 180 AD

The Chinese were also pioneers in the mechanization of the fan. Around 180 AD, the famous Han Dynasty inventor Ting Huan developed a rotary fan with seven wheels, each 10 feet in diameter, driven by hand, with which a single man could cool an entire hall.

Later during the Tang dynasty (618-907) water-powered rotary fans were being used in palaces for air conditioning, and in the Song dynasty people seem to have come to appreciate more and more the cooling effect of the artificial draught of air.

Later, rotary fans were used not only for cooling but also for ginning grain and ventilating mine shafts. Wang Zhen’s 1313 agricultural treatise Nong Shu also depicted a complicated Chinese rotary fan windmill (although the earliest illustration of a windmill is from a Han dynasty tomb model dated to the 2nd century BCE-2nd century). Following these innovations, the windmill was finally introduced into northern China in the early 13th century via the Jin dynasty, during the late Song dynasty.

Fans in China have a long history. Probably the oldest Chinese fans discovered to date are two woven bamboo fans (2nd century BC) excavated from the Mawangdui Tomb near Changshi in Hunan Province, but fans certainly existed in China long before that date.

This is a duplicate of the Western Han (202 BC-8 AD) long-handle bamboo fan excavated in the Mawangdui Han Tombs in Changsha of China’s southern Hunan province, which is the earliest evidence of fans made of bamboo that has survived to the present day.

Housed in Hunan Provincial Museum, the original has a long wood handle attached to one side of the kitchen-knife-shaped panel woven with narrow bamboo strips. Patterns similar to ox horn can be seen in the center of the panel, and both the handle and the edge of the panel are bound in silk fabric.

The most important function of long-handle fans was to provide shade from the sun, hence the name meaning “shade fan” in Chinese. Such fans became necessary apparatus to “shade the face” for the nobilities during outing in ancient China, and there were strict regulations on the usage of them.

The rules and regulations of the Zhou dynasty (1046-771 BC) stipulated the exact numbers of fans allowed for emperors and nobilities, for example, eight for emperors, six for dukes, four for ministers and two for general officials, as a sign of different classes.

The First Folding Fan Appeared in Japan in 9th Century

According to some sources, the folding hand fan was devised in Japan in the 9th century and later exported to China. However, it is the subject of legends in both countries. The Japanese believe the fan was inspired by the folding wings of a bat, while the Chinese think it was inspired by a woman fanning her face mask at a festival.

Japanese hand fans were originally used by the samurai class and Japanese aristocrats. Originally, they were used as writing materials to convey messages, as teaching aids, as status symbols, and even as weapons.

They were not used for cooling, nor were they intended as craft or decorative items. Japanese hand fans were to be kept closed and opened only when absolutely necessary.

Ancient Japanese tombs from the 6th century CE provide us with the earliest visual representations of fans in the form of drawings. The folding fan is thought to have appeared in Japan sometime in the 6th to 9th centuries. The first Japanese folding fans were called Akomeōgi (衵扇 ), after the dresses worn by Japanese court ladies, the akome.

The Song Sui (History of the Song), one of the official twenty-four histories of China that recounts the history of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), speaks of a Japanese monk named Chōnen who gave the Emperor of China a set of fans (twenty wooden-bladed fans (hiōgi) and two paper fans (kawahori-ōgi) in 988.

In the 11th century, Korean envoys brought Korean folding fans, known to be of Japanese origin, as gifts to the Chinese court. During the Heian period (794 to 1185 CE), folding fans became so popular in Japan that laws were enacted to restrict decorations on paper fans and hiōgi. The fans are made from thin strips of Japanese cypress (hinoki) and thread. By law, the number of wooden strips should reflect a person’s rank and status.

Japan became famous for the quality and beauty of its hand fans and began exporting them to China in the 15th century AD. Through trade and the Silk Road, the fans quickly spread to Europe, where they were highly sought after as decorative works of art.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, many European women from all walks of life wore a folding fan as part of their daily wardrobe. Today, the folding fan is one of the most convenient ways to cool off. It is very practical and does not require batteries or an electric charge—a simple solution to keep cool in the summer.

Hand Fans in Europe

Archaeological ruins and ancient texts show that the hand fan was used in ancient Greece at least since the 4th century BC and was known as rhipis (Greek: ῥιπίς).

The oldest known fan in Christian Europe was the flabellum (ceremonial fan), which dates from the 6th century. It was used during religious services to drive insects away from the consecrated bread and wine. Its use has died out in Western Europe but continues in Orthodox and Ethiopian churches.

Roman women had fans, and the British are also known to have used round fans. A sculptural tombstone in the Carlisle Museum shows a lady (c. AD 250) holding a large round fan with radiating ribs.

Further evidence of this type of fan can be found in a Roman sarcophagus from the 4th century AD. It would appear that the fan has had a dual function in fashion since antiquity: that of a status symbol and that of a useful ornament.

Hand fans did not exist in Europe in the High Middle Ages until they were reintroduced in the 13th and 14th centuries. Fans from the Middle East were brought by crusaders and refugees from the Byzantine Empire. Portuguese traders brought them from East Asia (China and Japan) in the 16th century, and fans became universally popular.

The fan became especially popular in Spain, where flamenco dancers used the fan and extended its use to the nobility. European fan manufacturers introduced more modern designs and brought the hand fan in line with modern fashion.

In Apalachicola, Florida, in the 1830s, American physician John Gorrie (1803-1855) blew air over a bucket of ice to cool hospital rooms for malaria and yellow fever patients. This was a prototype of modern misting fans.

When President James Garfield was shot in 1881, U.S. Navy engineers developed a combination fan and ice sheets that lowered the temperature in the dying president’s room by 20 degrees – using 436 pounds of ice per hour.

1882 – Schuyler Skaats Wheeler invents the electric fan with two blades and a new era of cooling begins: